Sarah Hill's

"'Blerwytirhwng?' The Place of Welsh Pop Music": Book ReviewThe emphasis here's on the location rather than the notation. This Cardiff musicologist does nearly nothing to let you know what the bands and musicians in the Welsh language over the past forty years sound like, but she does plenty to explain their cultural significance. This monograph, therefore, addresses not the curious listener but the diligent scholar who wishes to place contemporary Welsh music--mainly rock and some folk and reggae-- into the frameworks for Cultural Studies pioneered by Stuart Hall and Raymond Williams. As one who confronted the borders between England and Wales himself, Williams' categories work well. Hill expands his trio of dominant culture, a residual response, and oppositional ideology with the added "alternative" category. She threads these processes into the songs of various Welsh-language artists from the mid-60s up to the end of the past century.

The early chapters emerge identical to a thesis, as Hill documents the theories upon which her study's based. While Frederic Jameson luckily earns only a single tortured citation, Doreen Massey's power-geometries and John Street's rhetorically grounded political analyses do slow the presentation to the deliberate pace of the lecturer's seminar. While these references do support her scholarship, the amount of detail given in these two-hundred pages of text proper to the background and models for her study appears better suited to a dissertation than a book meant for a slightly wider readership. Hill appends a useful chronology, but a suggested discography or annotated entries on artists for potential listeners might have been for many who close these pages a better use of the limited pagination probably allotted her by an academic publisher which charges a hefty price for this slim volume. She follows with chapters on each decade, before 1963, up to 1973 (a sign of the lag here when the first amplified band-- outside of a psych-era one-off single appeared), 1973-82, 1982-90, and the 90s. She concludes at the millennial mark, and the double-CD of "Mwng," the Super Furry Animals CD entirely in Welsh.

Pop here remains at its widest panorama. But, you must strain to hear it, rather than merely read about it. (It's a pity you cannot see much of it. A few monochrome photos must suffice. Sain's groovy DIY record sleeves, as hinted at by the Finders Keepers label reissues in their "Welsh Rare Beat" series co-curated by Furry singer Gruff Rhys could have brightened these grey columns of print considerably, given the astonishingly high cost of this slim publication. Those LPs deserve an on-line archive; no study of the label exists outside Welsh. Logically, yes: that summarizes the whole state of the Welsh pop scene regarding the wider world. Still, poetic justice and marketing research aside, perhaps the WRB culture will underwrite an English-language "crib" for us?) The survey gains energy with the arrival of folksinger-activist Dafydd Iwan. The roots of the Sain label gain attention as well as Geraint Jarman's late-70s trilogy of astonishingly realized lyrics confronting the battleground between Welsh-speaking enclaves, non-Welsh-speaking residents, and English-dominant settlers. Another testimony to the small-scale nature of Welsh music can be glimpsed when we find Jarman and his band, emerging around the same time as The Clash, became the first professional musicians able to make a living solely from their music. This chapter, to my surprise given my never having heard Jarman or known but a cursory mention of Welsh dub, intrigued me for its close readings of his gripping lyrics that Hill translates and explicates thoughtfully.

Datblygu, whose sound Hill barely notices (it resembles Mark E Smith's The Fall), has in Dave Edwards a talented tortured voice. Paeans to bleak economics, failed love, and complacent Welshness all leap off of the page as much as Jarman's verses. Hill rightly ties into Roland Barthes' definition of the "grain" of the hand, the body, the voice "the whole carnal stereophony" of Edwards' vocals. Y Tystion's duo cleverly updates Gil Scott-Heron's "The Revolution Will Not Be Televised" to lambast, like Datblygu, the

"crachach" (the word's oddly absent from this volume) establishment which militant youth perceive as having commandeered the gains of the 1960s rebels such as Iwan and settled into the Caerdydd comforts of Radio Cymru and SG4. While Welsh can be broadcast into not only TV and radio but now the Net, whether or not the angrier voices of discontent can find their Cymric shout-out remains to be seen-- as with the rest of the globe given the state of our networks. I'd be intrigued to find how indie artists fare in Wales and Welsh with MySpace, filesharing, and raves, but these outlets either postdated Hill's forty-year limit or were beyond its scope. Certainly, much of her investigation reproduces lengthy lyrical excerpts in her engagingly blunt translation that express not only Iwan's "Carlo" but embittered disdain and eloquent frustration of those from post-punk, into hip-hop, and raised unwillingly under 'Magi' Thatcher.

Hill finds that by the time the Blair-era Cool Cymru manufactured the pop hits by Catatonia, Stereophonics, and Manic Street Preachers, the florescence of the Welsh scene had appeared, within Britpop, rather short-lived. It appears that the woozy decade of Oasis may have calmed the counter-assault. Welsh bands for the first time gained indie cred at least, by being found outside Wales at last. Yet, speaking for myself as a listener, the barrier of Welsh for an Anglo-American audience continued, all too appropriately, to be a challenge that trapped its makers on Ankst and Crai.

For my money, the more textured and experimental psych-pop of the Furries, and (far too little noted here) the lysergic folk of Gorky's Zygotic Mynci proved more durable. Hill glances only at Gorky's and you'd be hard pressed again-- as with nearly all of those singers and instrumentalists featured-- to have any clear idea of what these groups sound like at all. Hill fails to include any of GZM's Welsh-language lyrics and that band's move in and out of Welsh on their later CDs goes only generally mentioned in a couple of vaguely detailed paragraphs. Because her study by default stresses the lyrical expression of cultural ferment and political agitation, economic unrest and social stagnation, the tones and the tunes often get drowned out by the recitation. Hill places many of the sounds of Wales within their Anglo-American perceived patterns. However, unlike its folk tradition, Welsh rock and pop influences appear for her more distinctive as verses rather than chords.

Irony, Hill argues, displays a culture's security. If one engages in self-parody and one wags a finger of constructive criticism, then one's predicament emerges as a virtue. Hill adapts to Datblygu's predicament Terry Eagleton's "The Idea of Culture." Eagleton notes: "That someone in the process of being lowered into a snakepit cannot be ironic is a critical comment on his situation, not on irony." (155; original pp. 65-6) Edwards, Jarman, or Y Tystion can rebuke their addled countrymen and women for their plight simply because they have the leisure to consume and produce beyond the level of serpentine survival. (I wonder if being lowered into a coal mine daily produced once similar emotions?) Wales may have exhausted the "bliss" (Hill integrates Barthes'

jouissance to smooth effect here) of the era of Tryweryn marches, back-to-nature

Adfer protests, and

Cymdeithas yr Iaith Gymraeg language rights campaigns by the time of the mine closures and the failure of the 1979 de-evolution vote. Flower power faded.

The post-punk and rappingly bilingual youth of the Thatcher and Blair decades, by contrast, Hill contends, had to retreat into another confrontational strategy. Less enamored of idealism, less confident of revolution, 1980s Welsh musicians and singers enter into what Simon Frith labels (in "Sound Effects," cited here) as reggae's inspiration for punk. "It opened up questions of space and time in which musical choice-- the very

freedom of that choice-- stood in stark contrast to the thoughtlessness of rock 'n'roll; it implied, too, a homelessness-- this was choice as terror." (136; original p. 163) Note the delay between British and Welsh punk and rap-- this echo pattern repeats that of earlier musical genres and trends.

This spiritual descent into sonic exile and existential chaos captures well, in my opinion, the psychic state of those of us who came of age post-1960s but who inherited the potential power of that Revival radicalism that rock music often exposed us to as politically latent and culturally inherent within Celtic identity. The existence of any Irish parallels gains nearly no mention from Hill, but observations might prove useful. As I have remarked on the lack of republican or nationalist connections that remain little examined, so the musical movements and linguistic shifts that tie Ireland to Wales demand more comparison and contrast.

Ultimately, and here Geraint Jarman's pioneering confrontations with his homeland jaggedly intensify the countercultural sentiments of Dafydd Iwan for an earlier Welsh activism, the echo of religion lingers. While the chapel, the choir, and the bardic tradition of metrical intricacy find little resonance in pop music, Hill makes a surprisingly cogent case for the parallels of Rastafarianism and Welsh Nonconformity. Not on the surface or even their fundamental and obvious differences, of course, but for their mythic spells coded within a cultural patrimony. A legacy opposed to the British, the imperial, and the colonial. I cannot drift too far here, and I note that Y Tystion's later quoted with a line that accuses Henry VIII of eradicating Wales' historic faith. But, doctrinal realpolitik and regal machinations aside, Hill's inclusion of a 1996 Lawrence Grossberg interview with Stuart Hall from 1996 makes a convincing claim.

Hall explained how the religious social formation may be "valorized," and how the various "cultural strands are obliged to enter" there, even the political movements that strive towards popularity. Communal consciousness first emerged within religion in such arenas, so the people have been "'languaged' by the discourse of popular religion.'" The narrative they construct may be clumsy and tainted. But it's the first step towards making sense of one's own story, as a community. The Rastafarians, Hall continues, turned the Bible upside down. Not a line of continuity with their invented past, but a reconstruction: "they

became what they are." (130; p. 142 in "On Postmodernism and Articulation" in David Morley & Kuan-Hsing Chen, eds.

Stuart Hall: Critical Dialogues in Cultural Studies.) Hill elaborates how black Caribbeans did the same upending with the King's English into a creole, into their linguistic expression of a form matching content for simmering rebellion.

Later musicians often diminished in political intensity or skirted any explicit linguistic debate. The Super Furry Animals may have drifted, as with Catatonia and Gorky's, into an Anglophonically preferred style of more predictable delivery. Their melodies all became more accessible, more mainstream, and perhaps less distinctive as they became less quirky. Most critics have remarked upon the fall-off or steady-state in later 1990s, major-label, quality in all three bands. (Only SFA continues at this date, although solo efforts by Gruff Rhys of SFA and Richard James, Euros Childs, and John Lawrence from GZM have all merited attention the past few years.) Hill concludes her study with "Mwng," released 2000. SFA tunes here gained by their modesty, not as bold as their funky danceable mishmash, but more textured and sunny.

Obviously, irony and self-critique may survive in today's Welsh pop artists. Hill ends her study prematurely, with the symbolic statement of "Mwng." (She nods to this decade only in her penultimate paragraph.) Subsequent developments in the major Welsh artists I've mentioned, and the emergence of lesser-known ones, might have complicated her neat arrangment. A deeper examination of irony as expressed more profoundly in not only lyrical presentation but musical contexts-- present early in Welsh pop and rock and folk even in the 60s under primitive recording conditions that far lagged behind British studios-- and richer contexts of pan-Celtic solidarity (although Brittany gets a cameo entrance) would have enriched Hill's study. She incorporates dense jargon into her exploration; early on this slows her pace down. Yet, she manages well her case studies of musicians, sprinkled with her own first-hand interviews. She's able to incorporate sensibly even an overly familiar "third space" hybrid model from the ubiquitously quoted Homi Bhabha. The book ends with her repeating the phrase that opens the book and provides its title.

Yet, Hill rushes past a minor, if relevant, insight that connects her book's opening paragraph to its closing one. "Blerwytirhwng?" came about as a song when SFA still sang mainly in Welsh. Hill does not elaborate that 1995 EP on which it appeared took its own moniker from the LlanfairPG-abbreviated Guinness-record breaking, or setting, railroad station that marks our world's longest place name, in remarkable concatenations of Cymraeg. Hill answers the question of her book's borrowed title by tentatively taking stock post-millennium, and post-Welsh Assembly. "And if the answer to the structural question,'Blerwytirhwng?' is 'that in-between space', it inspired the type of assertions of identity noted in the preceding pages." (208) This playful confrontation between the English we use and the Welsh they know marks the borders crossed in what a later song opted for as "The International Language of Screaming." Here, indeed, the question of "whereareyoubetween" gets at last a deservedly non-theoretical, jargon-free, spirited yet ironic call-and-response.

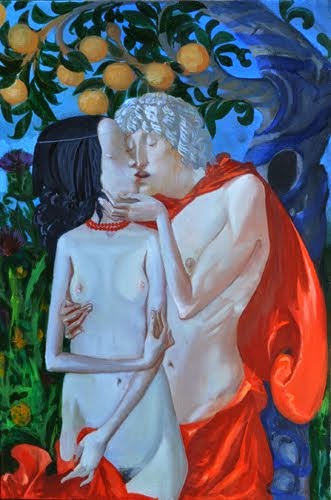

Image: cover of first volume of the "Welsh Rare Beat" CD compilations of late-60s/ early 70s Sain-label Welsh-language folk, pop, and psych.